I attended the Swedish Research Council’s annual symposium on artistic research on November 27th and 28th, and while there gave a presentation I had called «surviving Bologna». The talk – and the slides – were in Norwegian, but I have translated the slides, and post them here with some comment (since they are a little cryptic on their own).

I will emphasize: this is not a transcript, and I was a little more detailed and a little less flippant when actually presenting. But the content is more or less the same.

Not much to say about this one; I introduced myself and The Norwegian Film School.

Wasn’t the European education landscape lovely before Bologna? Wild, varied…and somewhat unpredictable.

This got a laugh. And, I’ll admit, I hoped it would.

It’s a fair depiction of how I view the aims of the Bologna agreements: create a uniform landscape where the «product» – the students – are ready for commercial exploitation. (i.e. the labour market).

I started working at the Norwegian Film School in 2009, and around the same time we received word that all arts educations in Norway were going to have to adhere to the new national regulations derived from the European Qualifications Frameworks – the product of the Bologna agreements.

We determined, rather quickly, that we needed to define this turf for ourselves, rather than sitting back and waiting for someone else to do it for us. Most likely in a way we would not appreciate… We did, however, have to teach ourselves some new terminology like «learning outcomes» and «Blooms taxonomy» as we felt we needed to master this language ourselves if we were going to make good use of it.

This also meant delving in to the relationship between conventional academic education and fine arts education.

The more we looked at it, the more apparent it became that our approach to education is fundamentally different from what one finds in (most) academic programmes.

I probably should have put quotes around the word «common» here, but regardless:

As far as I know, the classification of higher education done by the OECD in 1973 was the first attempt to compare higher education systems around the world. One unfortunate byproduct of this work was to place fine arts as a subset of humanities, effectively reducing the importance and autonomy of art schools connected to universities. While there has been much work done the past 15 years to change that classification, it represents a mindset we still encounter every day.

As a result we needed to spend a lot of time and effort creating a new landscape.

In this view, fine arts education is completely autonomous from and parallel to academic programmes – although we are naturally still part of the education landscape. The important point is to make it clear that much of what is applicable to one is not applicable to the other (although there is naturally some overlap as well)

Just claiming a difference is not enough, of course. It has to be clarified.

The $64,000 question.

We can begin to answer it by looking at the way learning outcomes are structured.

Knowledge is key to all education, on some level. We take «knowledge» very seriously indeed. Not only are many disciplines in filmmaking extremely technical, working on a film set can potentially be fatal if people don’t know what they’re doing. Both Norway and Sweden have seen deaths occur on film sets in recent years.

Add to that people are working with electricity, power tools and construction, traffic…there is a lot of stuff filmmakers have to know.

But – we never formally test the students in what they know. The have to demonstrate knowledge constantly, but they will never be tested in it.

Skills are another important learning outcome under the EQF, and given that filmmaking can be viewed as a skilled profession, acquisition of skills can also be seen as important. And indeed, operating sound equipment, setting proper lighting, creating an appropriately distressed look on the walls of a set; these are a small handful of the many skills Film School students are expected to learn and, in some cases, master over the course of their three years.

Again, as with knowledge, however – their skills will never be formally tested. There is no lighting exam.

How can this be? Well, quite simply, we are not a professional school; our mandate does not end with the skills our students acquire – it begins there.

And that is what «general competence» is about, isn’t? What can the student do with their knowledge and skills.

Although…we never really liked that word «general».

«Artistic competence» is much more telling, and gives us a chance to define what it actually is the students will be tested in (more on that later).

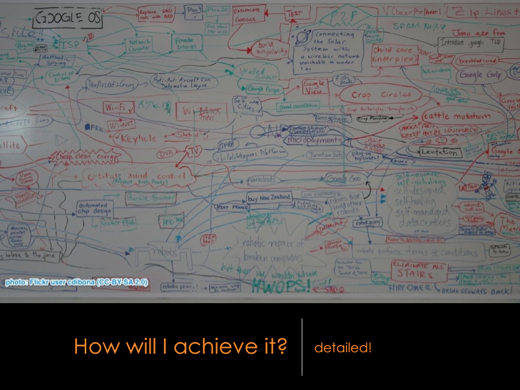

Once we had set the ground rules on how we approach learning outcomes, we need to define the learning outcomes themselves. This was a time-consuming process, and involved going though lesson plans, placing them in some kind of order, identifying holes, rewriting, hounding teachers for revised plans, rewriting those…

In March of 2011 we had a revised and updated description of the Film School’s study programmes.

That left a small problem we had created for ourselves.

Just how does one test and evaluate artistic competence?

Luckily, we have the appropriate tool. Years ago, the Norwegian Film School did what artists around the world have been doing since the origin of art: we stole a good idea from someone else and made it our own.

This is the «hensiktserklæring», which can be translated as either «declaration of intent» (more literal) or «statement of intent». I prefer the latter, primarily since the «declaration» seems unnecessarily bombastic.

For every production exercise the students make throughout their studies at the Film School, the students must write a statement of intent. Early in the studies these are quite simple, but as they progress through the programme they become more and more elaborate and detailed.

We (the teaching staff) put together the teams (one member from each of the disciplines we teach). Each team has to come up with a collective statement of intent and each individual team member must then write his or her own. These are written with guidance from each students’ teacher, and must be completed before the main creative work begins. For example, a director will hand in the statement of intent before principal photography begins, while the sound person (who will do both production sound and post sound) will hand hers in once she has seen the locked picture edit.

So – what goes into this thing?

First of all, the student needs to describe what she wants to achieve with this exercise – artistically / creatively. We give the students fairly specific tasks for the production exercises, and so they are already set on a fairly narrow path, but there is still a fair bit of leeway to be creative and express oneself artistically.

The key is that they are specific; the example I used in the presentation is «I want the audience to feel sad, even cry, at the end of the sequence.»

Ok. How?

This is the key to an effective statement of intent: the how.

«I am going to work with my actors to help them find a way of conveying the pain the character is feeling without slipping into cliched gestures.»

«I will find use a still camera with only subtle movement that finds a framing that leads the viewer closer to the character and their emotional state.»

«I will create a soundscape that gently brings the audience into the characters head at the same time as the camera brings us physically closer to him. I will highlight this with instrumental music that is melancholy without being sentimental.»

All made-up examples, but they give an idea of what the statement of intent could contain.

We are extremely rigid about never commenting on the «quality» of a finished production exercise in an evaluation situation. To put it bluntly: we leave it to the film critics to opine about whether a film is good or not.

What we do it read through the statements of intent and discuss and analyse whether the intent has been achieved. Why and why not are key questions. A good quality evaluation situation can only occur if the statement of intent has been specific – and ambitious enough to allow for the possibility of failure. If students never fail, they’re not trying hard enough…

Procedurally it’s simple: the whole class and all the teachers gather; we see the film and hear the statements of intent read out loud. We then discuss these statements with the members of the team. Often another film team will be assigned the task of leading the discussion, both to ensure that everyone participates in the end and also to ensure that the students get to speak first.

Invariably it takes a few months for the students to get the hang of this process, but generally they become quite adept at it during the second semester of their studies.

A long-term benefit of this practise is that it teaches the students to reflect over their own artistic practice constantly, leading them to become more confident and skilled artists.

The final stage was to define the structure of the educational programmes at the Film School.

The Norwegian word here is «emne», which, depending on the country you’re from, could be «subject» or «class».

You take a certain number of classes throughout your degree programme, with some electives along the way, and this way construct a programme that leads to a specific degree. Most of these classes, or subjects, are relatively self-contained, with their own set of requirements for successful completion.

At the end of each one you get a certain number of points or credits, and when you have enough – you graduate.

Not so at the Norwegian Film School. Although we on paper do have subjects, these subjects are fluid and blend in to each other. They are integrated, and none of them are completed before the entire programme is completed.

It is only at the end, after completing the 3-year, integrated whole, that you will have competed all the subjects.

Which, of course, means there is only one exam. At the end, and it’s for the whole pot of 180 ects credits.

The basis for the exam is the examination film, a 25-minute dramatic film the students have made in teams the final year. In addition, all disciplines other than director and producer have a personal project they have completed which gives them an opportunity to explore some aspect of their specific discipline in more depth.

As with production exercises, the statement of intent is key. The film will not be judged on some theoretical measure of quality, but the students contribution is judged on the basis of their specific and detailed intentions.

What the exam really tests in the end, is: has the student been able to use the knowledge and skills they gained to develop as an artist?

Each student should have a much greater understanding of what kind of artist they are, what their strengths and weaknesses are, where their potential lies. Insight is key, both for developing as an artist and, more prosaically, for passing the exam.

What about the other way around? How does the Film School develop?

For every workshop, every lecture, every production exercise: students give us feedback, most often written feedback. The purpose is twofold: we believe that when students give feedback on a given workshop or other module, they raise their own awareness about what they’ve learned.

The other side of it is we can constantly monitor what’s working and what isn’t, and dynamically adjust the course of the education. We use this feedback both to adjust what’s coming for the current class, and of course to plan an altered course for the next class.

As a result, we never have successive groups of students who have identical experiences – although the broad strokes are certainly recognizable.

Ok, so this slide didn’t really work.

I tried to draw an analogy between being out on a dark night experiencing a meteor shower and both being awestruck by the beauty and gaining an awareness of your place in the cosmos, and the experience you get when faced with great art. I then went on to say we want to produce artists who can give an audience these experiences.

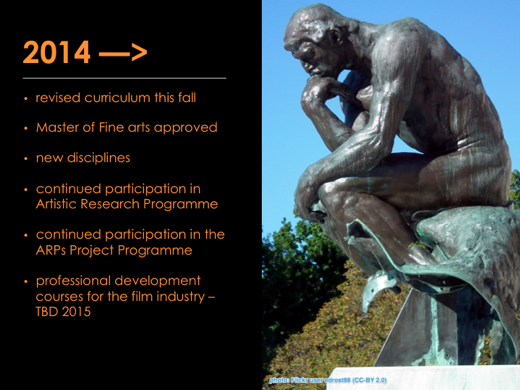

A little bit about what’s next for the Norwegian Film School.

And referring back to the flowers at the beginning: we want fine arts education to partake in designing the landscape. It has to be done by people who understand how this kind of education works and what it needs.

There wasn’t much time for questions, unfortunately.