I’ve got some time on my hands these days, and it’s time to pick up the film school pedagogy thread again. As I’ve posted earlier, I worked with a group of faculty from Nordic film schools in 2015 & 16 to develop a training programme for filmmakers teaching at film schools. Subsequently, I translated this to Norwegian, and completed a first cohort among our own staff in the school year 2018-19. I am now working on taking that experience and developing a curriculum for a second cohort.

The intro module from the Nordic version is still a good starting point, and so I’m posting it here and will endeavour to follow up with some thoughts and new ideas.

The intro module looked like this:

The Artist as (Film School) Teacher

Pedagogical development for filmmakers teaching in higher education

MODULE 1

Introduction to the training programme

mandatory for all participants

1,5 ECTS – 5 weeks – approx. time usage (including own time) is 8-10 hrs. per week.

Introduction

This module will introduce all the participants in the “The Artist as (Film School) Teacher” pedagogical course to several aspects of film school pedagogy, basics of online learning, principles of peeragogy, and to the approaches to teaching practiced at the participating Nordic film schools. The module will combine video hangouts and webconferencing, synchronous and asynchronous online discussions with readings, videos and reflection assignments.

Module 1 is not a standalone course, but serves as the introduction for all the filmmakers working at the NORDICIL schools who need – either due to formal requirements or personal interest – insight into and practice with pedagogy and didactic methods designed for film schools. This first module will introduce the series of modules that make up “The Artist as (Film School) Teacher” and, most importantly, ensure that all the participants have the same level of comfort with the online environments, the vocabulary of film school pedagogy, and the principles of peeragogy.

Completion of this module is a prerequisite for participating in further modules.

Learning outcomes.

By the conclusion of the module, the candidates will have achieved the following learning outcomes:

Knowledge: The candidates will have attained

- An overview of the approaches to pedagogy practiced at the participating film schools

- An overview of various tools for online learning and interaction

- An understanding of peeragogy and the importance of personal learning networks in online instruction.

- A good understanding of “pedagogy” and “didactics”, “scaffolding”, pragmatist educational practice, constructivist educational practice, other commonly used educational practices.

Skills: The candidates will be able to:

- Critically reflect over and place own personal approach to education and training within a larger context

- Choose, setup, and maintain online identities for use in future training modules

- Build and use a personal learning network (PLN) and personal learning environment (PLE)

- Support other participants in a PLN

- Understand the uses of pedagogy and didactics.

General competence:

At the conclusion of this first module, the participants will be prepared for further participation in “The Artist as (Film School) Teacher” by both enabling them to attain a level of comfort with the online tools and environments that will be used and helping them gain insight into the role of the educator as distinct from the filmmaker.

Course Structure

WEEK 1 – Introductions

In week one, the participants will receive an email with instructions on how to create an online account with the chosen PLE for this module[4] . At each of the 8 participating schools there will also be a designated resource person[1] the participants can go to for assistance getting online. Once logged in to the PLE, participants will see the syllabus for the course, will be able to download list of fundamental definitions, and will have access to some readings and videos.

Tasks for the week:

- Log into the PLE and create a full profile

- Read and reflect on pedagogical approaches from the different schools

- Share reflections on own approach to teaching in the PLE

- Read and reflect on “What is peeragogy?”

- View and reflect on selected videos (TBA)

WEEK 2 – Environments

In week two, participants will start to become familiar with the various online tools that will be used throughout this and future modules. Several tools will be presented with both pros and cons, and the facilitators will explain why some have been chosen at this point and how they will be used. These include tools for online discussions (eg. Slack, Google+, Twitter, etc.), for video interaction and webinars (eg. Skype, Google Hangouts), and for creating and sharing documents (such as Google Drive, Dropbox, blog tools such as Blogger & WordPress).

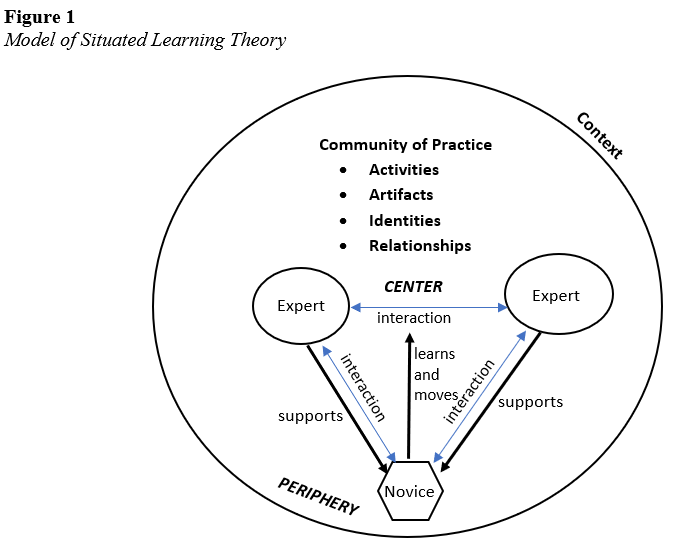

In addition, week two will see the introduction of basic learning theories and their application to the training of creative talents in filmmaking. Key questions include “What does it mean to be be developing creative talent and how does this differ from professional training?”, “What is an experience-based educational approach?”, and “To what extent does training artists /filmmakers rely on tacit knowledge, and what are the educational implications of this?” These questions are introduced at this point, but developing answers to them is a project for several modules.

Tasks for the week:

- Participate in the first video hangout

- Participate in a synchronous online discussion using Slack, Twitter, or Google+.

- Comment on reflections from week 1; if necessary update own reflection based on feedback

- Read selected readings introducing basics of Pragmatism (Dewey), Constructivism (Piaget), and Social Constructivism (Vygotsky). Max. 20 pages total.

- Start a self-reflection/criticism of the selected readings.

WEEK 3 – The Personal Learning Network

Peeragogy depends, as the name suggests, on interaction with and support from peers, and in this course the peers are film school teachers spread across 4 countries with different languages, representing 8 schools with different approaches in 6 cities. Reliance on online tools for building and supporting a peer network is absolutely necessary and a primary goal for week three is to help all the participants become more familiar and comfortable with using interactive online tools for establishing and building relationships in a learning network.

Tasks for the week:

- Participate in a video hangout

- Participate in a synchronous online discussion using Slack, Twitter, or Google+.

- Search for useful resources related to the week 2 readings and share any found to a central repository.

- Read selected sections of the Peeragogy Handbook and participate in an online discussion of peeragogy.

- Continue self-reflection/criticism of the selected readings, and begin referring to the additional resources found by module participants.

WEEK 4 – Towards developing a film school pedagogy

In week one

of the module, participants were asked to read and reflect on the pedagogical approaches of all the participating NORDICIL schools. At this point, they should feel comfortable enough to reflect critically on the approach of their own school and compare it with the other schools. In week four, the expectation is that participants will start to place their own pedagogical practices and thoughts within this larger context and engage in discussions with other participants in order to exchange thoughts and reflections.

Tasks for the week:

- Post own self-reflection/criticism in a public forum where the other participants can read and comment on it.

- Read, reflect and comment on the self-reflections of other participants, both from one’s own institution and from other institutions.

- Participate in online discussions (possible video hangout may be organised).

- Fill out self-assessment of course progress to date

WEEK 5 – Conclusions and final reflections

Module 1 is the launching pad for the subsequent modules, and a key metric for success is ensuring the participants are comfortable with both the technological environment and the foundational philosophies of peeragogy and film school pedagogy. The contents of week 5 will be very much determined by the results of the self-assessment survey completed at the end of week 4.

The goal for week 5 is to ensure the participants are familiar with their PLN and the tools for interaction and communication, and have developed a critical awareness of their own pedagogical practice and how it relates to a larger community of practice at the Nordic film schools. These are the key competencies that will form the foundation of the further modules in the course.

Tasks for the week:

- Participate in online discussions summarising the key takeaways from the module

- Update own self-reflection/criticism based on total feedback from others

- Complete online skills assessment

- Identify gaps in skills and knowledge and share a plan for filling these gaps

- Where applicable, offer peer support to others who share their learning gaps

- Complete final self-assessment and sign up for next module.

Organisation

Each of the

eight participating institutions has provided a participant in the NORDICIL working group that has developed “The Artist as (Film School) Teacher”. These 8 individuals are also the peer facilitators for Module 1, and will support each other in leading the various elements of the module.

There is no grade, and at the completion of the course participants will receive either a “completed” or “not completed” based on their active participation in all facets of the course over the 5-week period. A mark of “completed” is required in order to continue to the next module.